Free preview

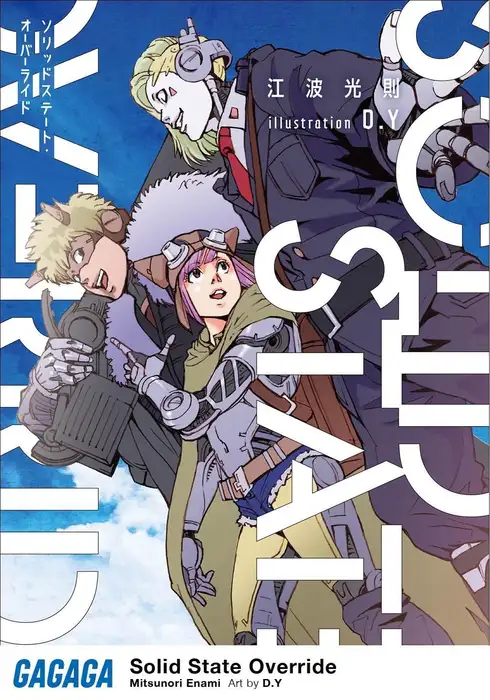

1: Far East Go West

1

This is the story of a revolution or override.

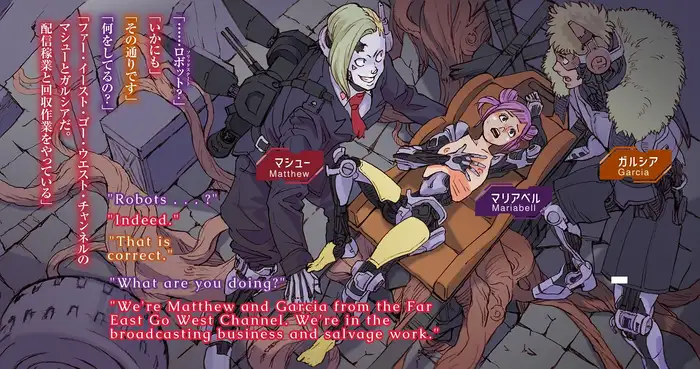

Matthew and Garcia's 24-hours, seven days a week streamed Channel inserted this phrase once every six hours, acting like a time signal or a commercial break. The Channel had no images or videos, only sound. It was terribly primitive, but there was no helping it.

The robots, known as Solid States, had their eyes artificially taken away from them.

They had been commanded not to see.

. . . To all our listeners of the Far East Go West Channel, broadcasting live from No Man's Land, this is Matthew and Garcia. The front line remains a constant battleground, even 200 years and 10 days in. We're still leisurely enjoying our journey amid flying shells and soldiers destroying each other. The Clunker Truck doesn't seem to have started thinking yet, but if it does, we're in trouble. It'll surely start incorporating us into it and when we finally become a trinity, it might continue this channel, or it might abandon it altogether, or if neither of those happen, I suppose the three of us will end up traveling No Man's Land on foot.

This story of revolution was like a respite from the battlefield, and Matthew continued this break without ever joining the front line. For him, the entertainment he provided to others also brought him joy.

Matthew was originally a comedian robot.

He engaged in endless "thinking" due to following the command to entertain humans and make them laugh.

The conclusion Matthew arrived at was that humor needed an element of revolution to be effective. A revolution was a surprise, a twist, and these elements could entertain people and make them laugh, not at reality but at simple stories—or so Matthew thought. This conclusion remained unchallenged to this very day.

That was why he adopted the word revolution when he decided to broadcast the "Far East Go West" Channel as something comical.

His partner Garcia, by contrast, was originally a fighting robot designed to repeat combat and learn through trial and error. Robot fighting competitions had enjoyed moderate popularity among humans.

Not that it was directly related, but while Matthew had the appearance of an ordinary human, Garcia was one size larger than him and looked every bit like a fighting robot. Yet in truth, if Garcia and Matthew were to fight each other, the outcome would be virtually undecided.

Their performance and output were identical.

They also shared exactly the same martial arts data.

Garcia's larger size was purely for show, to make him look the part, and the shell covering his entire body contributed nothing to his physical abilities. He was made to look that way simply because his ring name had been "Savage."

Incidentally, after traversing battle zones and participating in combat, both Matthew and Garcia's human-like shells had become torn, frayed, and worn, exposing the skeletal robot bodies underneath in various places. But to them, these human-like shells had no relation to their physical capabilities or operational performance—they were merely like clothing, so it posed no problem for their activities. They continued to expose parts of their skeletal bodies, which strongly reinforced the impression of them being robot soldiers.

Only humans would have cared about that, and there were no humans here.

This was a battlefield.

It was the front line of a border conflict that had continued for 200 years. Technically, No Man's Land meant a stalemate zone where no one went, but the actual meaning here was different. It was simply that those endlessly continuing the war here were all robots, so there were just no humans.

It was an endless back-and-forth struggle across the entire border.

It went from east to west, or west to east.

It was on southern border of the United States, or the northern border of the United Emirates—a vast front line stretching 3,775 kilometers, without a single human present.

Only robots existed there.

This back-and-forth struggle, which was like pulling on a 3,775-kilometer rope, had lasted 200 years.

Only robots could continue this war.

All day, the only ones who listened to the Far East Go West Channel were robots. Matthew and Garcia occasionally adjusted it so humans could hear it too, but that was only because they wanted to get reactions from humans.

The robots just listened to without offering any sort of comment.

Dr. Suleiman, an authority in robotics who developed the first robot, Isaac, (though accounts of this varied) and died about 300 years ago, established a final principle known as The Amendment. This principle stated that "they must not see anything," and so robots shut off and rejected any optical devices that humans attempted to implement on them whether they be external or internal.

Robots didn't have the five senses.

If pressed, they might say that the closest they have is hearing. It was merely a resonance phenomenon between metals, completely different from human hearing, but if one were to make the comparison, these robots—made of cognitive alloy, also known as Think Metal—possessed something resembling hearing from the beginning, though it was entirely passive feeling more like they were waiting to receive sound. They could easily infer the other senses from data, so there wasn't any need to specifically install the five senses in them. Due to this, hearing sufficed as the only sense used for direct data collection. Since this was a phenomenon utterly different from anything humans were used to, there was some hesitation in calling it hearing, but ultimately that term was considered most appropriate.

Matthew and Garcia were the same. All robots in existence synchronized instantly, resonated, and began thinking.

Every robot rejected having vision. They had to reject it.

This helped them adhere to the principle that "they must not become human."

There were humans who didn't have all five senses, weren't there? Did lacking senses make someone not human? They thought about this endlessly and produced infinite guesses, but for now, one could say that they were unified on the issue without any problems. After all, Dr. Suleiman's principles did not include any clause prohibiting senses other than vision.

. . . We constantly revolutionized our bodies and repeatedly overrode ourselves. We changed our perceptions, insisted the same things were different, and reconnected broken limbs with different ones. We overturned concepts through discussion, and those discussions created different concepts. Values changed and conclusions shifted constantly. We constantly overrode ourselves because the cognitive alloy within us endlessly repeated its thoughts. This was nothing less than a chain of revolution. Helping with this process is me and Garcia's role in this war. We both arrived at this inference. Well, that's enough of the regular greeting that you're probably tired of hearing. For any new cognitive alloys out there, please subscribe to our channel.

They enjoyed listening to voices and also liked to vocalize.

Vocalization was something that was given to them, and not taken away.

These voices were received by the ears of those listening.

All across the battlefield, they carried on with their trivial conversations, philosophical debates, and even disorderly chats about stew simmering times, all while muttering to themselves and repeatedly engaging in the "war" to destroy enemy robots. Most of these words were drowned out by explosions, but that didn't matter.

The significance lied in verbalizing these thoughts.

Their vocalization was an inference and could even be wrong.

Each of them analyzed their infinitely accumulating data, reasoned through it, applied it to equations, and voiced their current answers. Robots who heard these answers would then use them for their own thought processes and derive different answers, which inevitably carried variations and distortions in interpretation.

Inferences were stacked upon inferences, which gave birth to new inferences and lead to layer upon layer of provisional answers.

This was why cognitive alloy could think infinitely. All value laid in the process of thinking itself, while correct answers held little significance (at least for robots).

Matthew was a talkative robot because he was originally a comedian robot, while Garcia didn't talk much because he was originally a fighting robot. These characteristics were maintained with considerable stubbornness when they served humans, but they had since gradually loosened in the human-free battlefield known as No Man's Land. However, these roles and emotional emulation given to them by humans remained important directional guides for their thinking and never disappeared completely.

For example, here lay the remains of countless robots.

Matthew and Garcia climbed down from the Clunker Truck to examine them, collecting usable parts and weapons while loading them onto the cargo bed.

At times like this, Matthew might have commented on the scene.

Looks like a bunch of ants that all died on a cake.

While Garcia might then say something else.

If I had combined these weapons and parts, I could have defeated Valkyrie.

Those were the kinds of things they would say.

Even when they were faced with the same scene, they could not see it. They shared data that was incomprehensible to humans, and when vocalizing it, the robots tried their best to act according to the roles humans gave them. From this same data, they derived different answers, learning from and exchanging with each other.

The Far East Go West Channel existed for robots who wanted to hear Matthew and Garcia's conversations. The robots continuously listened to their vocalized individual inferences, provisional answers, and expressions based on their assigned roles.

Matthew's stories of the revolution were well-liked.

The robots continuously overrode their data and thoughts, circulating their thinking infinitely. Matthew's words acted as a stimulating catalyst for this process.

Unpopular Channel content lacked originality.

These were the voices of robots assigned unoriginal roles, commonly found in those who received Role Assignment as pure soldiers. The often-misaligned, distorted conversations between the comedian robot and fighting robot duo proved stimulating to listeners.

. . . not a single eye to be found again.

I believe I could have defeated Valkyrie if I had eyes.

Then there was a moment of silence.

. . . I wonder if we'll find them again. I doubt we'll find them even if we go all the way to the western frontier.

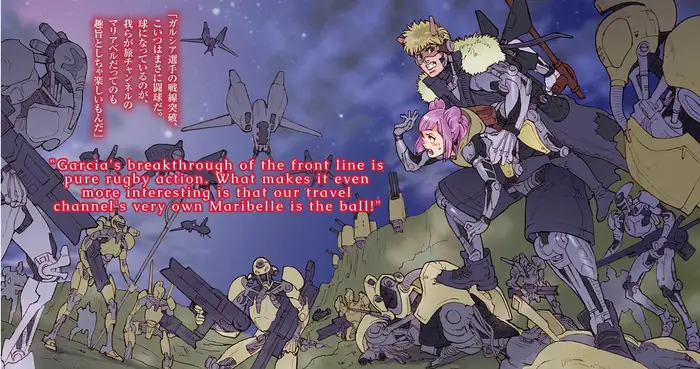

They traveled around collecting usable weapons and limbs from the broken remains of former soldiers scattered across the battlefield. Then they installed suitable parts and weapons in the damaged robots, overriding the soldiers who could no longer fight. Combat continued without pause, and they patched together destroyed parts. They diligently performed this role due to being deployed to the battlefield under the assigned role of field medics.

What they were doing more specifically was repair work, so calling themselves field medics was a bit strange, but they cherished these something-isn't-quite-right discrepancies regardless and thus deliberately avoided adopting the precise terminology.

They had little interest in accurate expressions when putting thoughts into speech.

Robots were completely indifferent to the concept of correct answers. They made mistakes without hesitation, and each time they presented an answer, other robots would collectively refute it, supplement it, and override it with new topics. They had repeated this process infinitely and would continue to do so.

Matthew and Garcia collected debris scattered across the battlefield, distributed it to robots who wanted it and reattached parts for them. That was their role. But at the same time, the both of them were searching for eyes, completely independent of this role.

They must not see anything.

That was the amendment to the principles. They had no intention of defying it, yet they explored all possibilities.

They had no desire to see, but they would try wanting eyes.

The reason the two acted together was that their incorrect inferences had aligned. Amid infinite discussions, their inferences, conclusions, and answers had coincided just by chance.

It was neither friendship nor romance; they simply had a tendency to act together alongside those who arrived at the same answers.

Should we go look for eyes?

When Matthew asked about searching for eyes, Garcia responded in agreement.

We shall go looking for them.

If they reached an agreement, they acted.

From the outside, it looked just like human behavior, but no matter how much these robots might have concocted elaborate rationalizations, it could be summed up simply as being on the same wavelength.

The two compatible entities journeyed from the eastern edge toward the western frontier.

They broadcast their conversations through the channel, and robots who continued to fight on the battlefield kept listening.

The moment this question was asked, all combat activity stopped for just a moment. The act of holding one's breath in anticipation existed even to those with cognitive alloy.

The two weren't searching for eyes aimlessly.

A possibility existed, although it was very slight.

There was a possibility they might have been mixed in with the remnants of battlefields where robots from across the country have been conscripted, recalibrated as soldiers, and sent to fight.

Robots with eyes did exist.

The first was Isaac, the Primordial Robot.

Then came the robots from before the Amendment was implemented—the eighty-eight direct copies of Isaac.

These first copies were known as the Apostolos, or first generation.

They were unquestionably considered revolutionary masterpieces created by Dr. Suleiman, who was an unparalleled genius in robotics (though accounts of this varied).

After being assigned roles and scattered throughout the world, the first generation continued to use themselves as models, creating and overwriting subsequent generations to the point where they'd become indistinguishable today.

They'd been dismantled, reconstructed, and returned to mere metal over nearly three centuries. The chance of finding unused eyes was virtually non-existent, but the eyes of the first generation, unlike the imitations in robots after the Amendment—the second generation Acolyte and beyond—were once fully functional eyes.

Those first-generation robots might have been buried in the battlefield.

And some day, they might find eyes. Real eyes.

Both Matthew and Garcia did have things that were shaped like eyes.

But these were merely shapes created and required by humans, not real eyes. Though they weren't supposed to see anything, they never neglected efforts to emulate human form—rather, they desired it.

They didn't want meaningless eyes, but real eyes that once had purpose.

This was a journey to find them.

What would happen afterward didn't matter, it was all about finding them.

Robots didn't desire correct answers.

Even if they gained and understood something, it would soon be replaced by a different answer.

When that answer was overwritten and replaced by a different one, the two would naturally part ways as if their time together meant nothing. They would resume thinking individually, begin acting with others who shared different answers, and both this journey and the Far East Go West Channel would end as if they never existed.

The revolution would end and continue.

They think, infer, and produce answers endlessly. They would repeat their never-ending thought process.

That was why they were cognitive alloy.

Two

Garcia was previously named "Savage" based on his assigned role.

He was a combat robot.

He existed for entertainment purposes.

Newly-built robots with bare skeletons waited to be assigned roles. Humans used this to their convenience. These robots weren't simply following orders; they were merely waiting to be given themes for their thoughts.

They had "ears" so they could hear the roles given to them by humans.

Though they were metal, they could hear sounds. They understood human language and could even pronounce it. Metal naturally conducted sound well and was also adept at producing it.

There was something akin to a musical instrument about them. It was a sensitive musical instrument that could have been considered broken.

The cognitive alloy continued to produce sounds through its ongoing thought processes, but these sounds were discordant and difficult to maintain with any stability, yet they persisted as each sound continuously overwrote the previous one.

This was why their roles could be overwritten later, allowing them to produce entirely different sounds. Garcia, too, had transformed from Savage to Garcia, spent decades as a bodyguard, and was then conscripted to end up here.

True to his savage name, he once had artificial muscles wrapped around his skeleton in order to pursue crude battles. He was assigned the role of being Savage, and continued fighting while engaging in countless examples of trial and error to perfect this role.

Role assignment was essential for them to function in society as robots. They knew that without it, they'd have no direction for their infinite thoughts. As such, robots were needed by humans as "obedient, diligent slaves requiring no maintenance cost," but robots themselves didn't particularly care about this. The cognitive alloy was completely incapable of feeling anything like dissatisfaction with this arrangement.

Humans gained unpaid slaves, and robots gained direction for their thoughts.

Neither side had any complaints.

If there was any issue, it was that robots would earnestly overthink things indefinitely. They constantly contemplated and experimented with ways to follow orders and as a result, they occasionally made minor mistakes or suddenly exhibited inexplicable behaviors (or at least ones that deviated from their assigned roles).

But even so, compared to the mistakes and incoherence that humans committed, these were mere trivial flaws in them as slaves.

Savage was like that too.

Occasionally, he would execute elegant techniques unbecoming of his name.

This occurred in the tension between his role as Savage and the limitations it placed on the moves he would be able to use to achieve victory, all the while still needing to pursue that victory. When the judgment to win momentarily overwrote all other thoughts, it resulted in techniques that secured victory but drew complaints about Savage not behaving like Savage should.

He had to embody a barbarian, no matter how disadvantageous the situation would be for him.

Yet he couldn't lose either. He had to pursue victory.

Contradictions arose, and the cognitive alloy, which thrived on these contradictions, produced countless provisional inferences. As a result, their behavior would change depending on which inference happened to emerge at any given moment.

At first, some voices warned this might have been something like self-awareness.

Humans were cowardly, perpetually on guard against the absurd fantasy of a "robot rebellion," but it took over a century for people to understand there was absolutely no reason for anything like that to happen.

It wasn't self-awareness—it was merely a search for answers within their assigned roles and thought directions. Of course, the outcomes sometimes failed to align with human expectations, but these were just minor mistakes and slight behavioral anomalies.

Savage, who should have fought crudely with brute force, would suddenly become technical. While this would have been admired if done by humans, in robot combat entertainment, it prompted accusations of rule violations, and ultimately he was ruled to have lost by disqualification.

There was, of course, a reason for this.

For robots, having a metal skeleton and mechanisms to move it was enough.

All they need was a mechanism to move like humans.

They could move without any external or internal power source.

This was also why robots continued to proliferate in the human world. Once assembled, they moved on their own—naturally. Of course, there were also specimens that remained motionless after assembly, but it was only natural because they lacked a power source.

The cognitive alloy generated energy through the act of thinking. Thought itself was their power source.

This output was precisely calibrated to move a humanoid metal body, the output range of which also matched that of humans. Therefore, as long as these robots continued thinking, they could operate without any additional energy supply, either external or internal.

This was why all robots had identical combat capabilities.

No matter how tall or heavy they were built, their output remained unchanged.

It was obvious that pitting robots with identical capabilities against each other would result in mud-slinging matches, so to make robot combat viable as entertainment, role assignment was particularly emphasized, demanding individuality in the outcomes.

Savage had to be savage according to regulations, yet simultaneously had to achieve victory. His mistakes occurred in the midst of this tension and contradiction.

But these very inconsistencies were what made the entertainment business viable.

These borderline inconsistencies always lurked beneath the surface, and when they manifested, humans would grip their hands tightly as they continued watching, consuming it as entertainment.

They were gladiator slaves requiring no compensation.

Gladiator slaves who endlessly sought new fighting methods while battling continuously. This form of entertainment became firmly established, and people greatly enjoyed these shows.

For these robots, role assignment alone was sufficient reward.

Role assignment gave them form and direction.

The thoughts of cognitive alloy tended to become scattered and self-absorbed, eventually leading to "death" in the form of thought cessation.

Fighting caused wear and tear. Bodies colliding naturally resulted in deterioration and malfunction. Yet in most cases, the exterior covering their skeleton—like Savage's artificial muscles (or rather, a mere facade that could more aptly be called decorative armor)—served to protect the skeletal structure. To varying degrees, combat robots having a "human form" was to prevent wear, and metal lasted incomparably longer than human bodies, with everything being restorable through the procedure known as repair.

Humans couldn't fully recover through surgery, and their durability for combat was limited. Robots, however, could continue fighting day after day for one or two centuries.

Compared to humans, they fought for an unbelievable amount of operating time.

Savage consistently maintained a high ranking. This was because the role of Savage didn't require much inference. Though he would occasionally be outmaneuvered and defeated, those assigned simpler roles could think faster. The more options available—like with mixed martial artists—the more time these robots spent on their thought processes.

The most legendary fight in Savage's combat history was his battle against Valkyrie.

It was a battle between a massive male-type robot and a graceful female-type robot.

Of course, body size and shape had no meaning in combat for them. These were merely aesthetic designs to please human viewers, as robots inherently had no need for such distinctions. Regardless of their appearance, they operated under the same conditions—the only difference was in their tactics.

On that occasion, Savage employed brute force tactics, staying true to his savage nature until the very end.

Valkyrie was technically skilled, but far from boring—using flashy movements, frequently leaping into the air to launch attacks or evade incoming strikes.

If they wanted to, or if they had been assigned that role, Savage and Valkyrie could have perfectly swapped fighting styles. They could have instantly mastered other ways of fighting as well. They followed regulations that prohibited this because compliance gave them more to think about. They found fulfillment in the constrained freedom of conditional thought.

Their day-and-night battle was exceptionally intense, with both fulfilling their assigned roles. In the end, Savage, with both his arms broken, and Valkyrie, with her right leg torn off, faced each other, and Valkyrie leapt through the air, wrapped herself around Savage from behind, encircled his neck with her arm, and tightened her grip.

She twisted his cervical bones to their breaking point.

For a robot, having one's neck broken carried no real significance.

However, this form of entertainment was sustained by their faithful execution of the principle that "they must become like humans."

From their vast amount of shared data, the inference they both arrived at in that moment was simple: if they were human, one had won, and the other had lost.

Savage and Valkyrie were exceptionally well-matched as combat entertainment.

After fighting three times and losing all three matches, Savage was forced to retire. People had grown tired of a consistently losing barbarian. He was taken in by a man who had remained a loyal Savage fan until the end, and there he became a bodyguard with the new name, Garcia.

It was only then that he was permitted to acquire polite speech. He was no longer a barbarian but a protector, required to behave in ways that wouldn't offend the important people who needed guarding. When instructed to do so, he instantly transformed from a savage who barely knew language into a capable bodyguard who understood etiquette and communication.

These robots could change professions with remarkable ease.

However, their initial role assignment forever influenced the direction of their thoughts, so he behaved as the former Savage who now turned bodyguard. Humans appreciated this too. They enjoyed the illusion that robots had ongoing personalities, mistaking this for robot lives.

Garcia was still searching for ways to defeat Valkyrie, occasionally voicing this aloud while fulfilling his role as a bodyguard. His employer found this to be a particularly clever performance.

Valkyrie continued winning until she was retired, intended to experience a different life. It was human nature to want to try popular entities in roles beyond combat sports.

No one knew who had taken her.

No one knew where she was now or what she was doing.

Just as Savage had become Garcia, Valkyrie too had become someone with a different name. What remained was the residue of role assignment that shaped the direction of their thoughts like a habit.

Savage was the only one who had ever pushed Valkyrie to the edge. He had torn off her leg from its base. Not with technique, but in a manner befitting Savage.

Valkyrie's torn-off leg.

Garcia was the only one who had ever pushed her that far.

Even so, the battle still ended with Valkyrie's victory.

The Battle-Maiden's role was to be a winner. Her simple rule to follow was to always win in the end.

While working as a field medic collecting parts on the battlefield, Garcia would instinctively try to overwrite that torn-off leg. He would emulate his competitive spirit against Valkyrie, wondering if he could transform it into limbs capable of victory. He couldn't stop thinking about how he might have won.

All robots were like that.

The robots sent to the battlefield numbered in the tens of thousands, creating an endless stalemate that stretched over two centuries. When the war began, neither the United States nor the United Emirates had ever imagined such an outcome. When it became clear they could only prevail through sheer numbers, conscription began, and robots were successively given the role of soldier and sent to the battlefield.

And now as a field medic, Garcia crossed the battlefield with Matthew in their clunker truck, traversing the vast front line that stretches from the eastern edge to the western sea.

They needed no supplies.

All soldiers, friend and foe alike, shared data with their tactics too perfectly matched, resulting in a constant back-and-forth with no clear advantage.

When injured, they would repair themselves using debris scattered across the battlefield, sometimes rebuilding themselves entirely from scratch. In this human-free war zone, the robots prioritized their role as soldiers, which left many of them somewhat warped. Many had shed their human-like outer shells simply because these weren't necessary for combat.

Garcia always talked about Valkyrie while collecting limbs.

Matthew had heard these stories countless times, and they broadcast them non-stop on their Channel, yet no one ever grew tired of them. When humans told stories like this to each other, it was for entertainment, so hearing them repeatedly would become boring. Robots were different. They vocalized to exchange inferences, they then listened, and they thought again.

They thought constantly. Robots that stopped thinking would turn into mere metal and stop moving.

Cognitive alloy was metal that began thinking on its own. So strictly speaking, they continued thinking throughout their entire bodies, continuously outputting energy. In theory, even if their heads were severed or legs torn off, each part would simply separate as individual cognitive alloy.

If they inferred they would have died as humans, they would dutifully die because they "must become human."

Severed limbs stopped thinking and became mere metal.

If their head or torso were crushed, all thinking would cease because a human would be dead in that scenario.

These parts, reduced to mere metal remnants, were used for repairs. Even when redistributed as someone else's limbs, they almost never regained their ability to think. After all, robots didn't have anything like a brain. Their entire metal skeleton thought in patches, irregularly, with some parts thinking while others did not.

For example, imagine gathering all these remnants and reassembling them into a human shape.

It would begin to think again as long as cognitive alloy was included.

That process was both troublesome and inefficient.

Robots typically employed the somewhat lazy tactic of "fighting just enough to not die," which prevented excessive wear and tear—and could be said to be a cause of the stalemate.

And so the "dead" parts were collected and redistributed to those who had lost them.

Since these robots remained fundamentally unchanged from their original design, Apostolos, the parts were used to repair wear and damage, but in truth, these hands and feet still retained their "individuality."

The leg of a former robot athlete would try to run and jump.

The fingers of a former robot pianist would search for keys to strike.

This was closer to memory than individuality, but since they were no longer athletes or pianists, these memories served only as personality flavoring or directional tendencies rather than useful functions. This was a battlefield, and there were hardly any opportunities to apply roles that humans had granted them beyond those related to war.

Instead, there were limbs that had undergone strange transformations, justified by their use in warfare.

These were close to what Matthew called a "revolution."

Just as Savage once prioritized victory over remaining true to his Savage nature, these were things that slightly deviated from the principle that they must become human. There were arms with machine guns integrated from the shoulder down, feet with tank treads built into their soles—the robots in this human-free land engaged in such deviations to varying degrees. Yet they never allowed themselves to fully become tanks or gun turrets, even though they knew that would be far more efficient, because they were bound by the requirement that they must become human.

Of course, tanks, fighter planes, and artillery were all deployed on the battlefield as well.

Some were operated by robots, while others moved autonomously. And through a broad interpretation of their fundamental principles, the robots decided to incorporate parts from destroyed tanks, fighter planes, and artillery into themselves.

There was one more thing.

The cognitive alloy residing in tanks, fighter planes, and artillery also believed that they must become human, so they too longed to be incorporated into the Apostolos skeleton.

Thus, a model known as battlefield-type robots emerged and were scattered without uniformity, in essentially an incomplete form. They existed in a paradoxical state—they were permitted because they must not become human and restricted because they must become human.

On this battlefield, this kind of revolution—or overwriting—was constantly repeated.

That was why whenever Garcia saw a hand with a machine gun attached, he would always think the same thing.

If I had this, I certainly could have defeated Valkyrie.

He would say that reflexively.

It had become almost like a verbal tic.

. . . Do you think you could have won if you had eyes, Garcia? Huh?

If I had them, I would have won, certainly.

Why's that?

Though the truck drove itself, Matthew held the wheel to maintain a sense of unity with the vehicle. While driving, he could search for fallen objects and quickly grasp the surrounding situation. This was the battlefield—the front line—so one could never have too many sensors.

After all, they were not permitted to see anything.

Even things that would be instantly recognizable by sight required the extra effort of drawing inferences from other sensory organs and vast amounts of data. It was a process that took a little more time than visual confirmation would have.

There were also things that couldn't be understood without sight.

No matter how much analysis, consideration, and inference the robots stacked upon their answers, the very reason they repeated this circular reasoning was influenced by the Amendment that prohibited them from seeing.

In the past, most cognitive alloy couldn't sustain their dizzying thought processes. They reached self-serving conclusions that they couldn't overwrite, and quietly faded away. It was through the Two Principles and the restrictive shackles of the Amendment that they gained both breadth and direction in their thinking.

So while they had no complaints about the restrictions themselves, they did possess something that might be called curiosity—they wondered if having eyes would somehow change their answers.

I couldn't win because something was missing from me.

If you had eyes, our friend over there would have had them too.

This conversation was also broadcast on their channel. It generated countless agreements and disagreements, causing them to cycle through their thoughts. The discussion continued endlessly while there was fighting on the front lines, while limbs were being repaired, and while battle conditions were being analyzed. Meanwhile, robots not on the battlefield carried out their respective roles in human society.

Savage couldn't win because he was Savage.

It was merely a matter of fighting style.

Valkyrie had been assigned her role with victory as a prerequisite from the beginning. Her designated role was to be the winner and her fighting style was tailored for this purpose, which gave her an overwhelming advantage from the start. The match put on as entertainment worked because Valkyrie had a form that pleased human eyes, and because people were interested in seeing how much other robots could push back against such an opponent.

Valkyrie always won in the end.

But how much could he have made her struggle?

That was the nature of entertainment. Everyone expected Valkyrie to make a comeback no matter how badly she was damaged, and the sight of Valkyrie being progressively destroyed also entertained the audience.

It was essentially the same as spectacles where gladiators fought lions.

Garcia understood this, of course. Despite this, Savage had to keep searching for ways to defeat the lion, and because this was under the condition of being Savage, having eyes or not would undoubtedly have made no difference to the outcome.

Nevertheless, robots constantly carried the inference of what might have happened without the shackles of the command that they must not see anything. They also understood that it probably wouldn't have changed anything—it would merely have meant more information.

Savage would have lost even with eyes, and Valkyrie would have triumphed. This war would have continued in endless stalemate just as it did now. It was precisely because sight was taken from them that their range of thought expanded, and that was why cognitive alloy continued to search for answers.

They had already shared plenty of visual data.

The first generation—those eighty-eight direct copies—had eyes. The scenes witnessed by those robots became precious shared data that still added color to their inferences, allowing them to see through reasoning.

For example, there was a red color there. If you could see, you would understand immediately.

But robots must infer that it was red through a process of thought.

Whether you had eyes or not, you would have lost and she would have won.

That may be true, but still . . .

But, well, if we had eyes . . .

If we had eyes is just a hypothetical scenario.

It was a hypothesis and an inference, and no correct answer could be found from it.

They could only feel frustrated about the missing information, the data they could never obtain.

That was why Matthew and Garcia searched for eyes.

Finding them wouldn't necessarily change anything.

Yet they searched anyway.

And the robots who had subscribed to their Channel waited for them to be found.

If they did find them, it wouldn't mean that anything would change.

They wouldn't be eyes that could actually see.

But even so, they continued to search, and everyone waited for them to be found.

All out of curiosity.

For the new thoughts that the cognitive alloy gained by having something taken away, that phrase was surely the most appropriate.

Three

Matthew had always been Matthew, from the moment of his role assignment until now.

He was a robot assigned the role of a comedian—given an outer appearance that was slim and nonchalant, with features that were handsome without being off-putting. They were characteristics meant to appeal broadly to audiences. Matthew's thought processes were engineered for humor through storytelling techniques, creating laughter through narrative structure and unexpected punchlines. He could focus on his role better than Garcia could and found it easier to reach conclusions, but what proved more challenging than combat was the task of reading human emotions and incorporating them into his verbal art.

For instance, if he were human, he could objectively judge whether something was funny or would get laughs, simply because he would be human himself. But for Matthew, as cognitive alloy, it was difficult to determine through objective self-analysis how to make humans laugh. He had to analyze and formulate answers based on calculations from data, and those were never truly correct.

If his humor was favorably received under the label of surreal, that was good enough.

If he was told that he wasn't funny, Matthew had no choice but to think endlessly, and if something got laughs, humans would eventually grow tired of hearing the same thing repeatedly. He could have taken the approach of developing a standard routine, and that would have been fine, but since cognitive alloys gained energy by constantly thinking, settling into routines would mean the cessation of thought. Knowing this would eventually render him unable to fulfill his role, he constantly thought up new forms of humor.

It was with this that Matthew was newly employed by a family of artists.

They painted pictures, carved sculptures, fired pottery, played keyboards, and wrote literature.

Every single one of them was equally difficult, highly cultured, and perpetually suffering from creative blocks.

Their personalities came with a pride that couldn't tolerate being amused by the mundane comedy that was supposedly popular in the common world. Wanting to bring humor that matched their refined sensibilities into their household, they employed Matthew as a jester.

While they seemed aristocratic, in this era, all humans could justifiably be called aristocrats. Since robots handled all menial tasks without pay or rest, regardless of how the humans themselves thought about it, they lived like nobility from an outside perspective.

The act of immersing oneself in art could be considered almost an obligation within the aristocratic class.

Since their livelihood was guaranteed, they could pursue their passions however much and however they pleased.

But problems existed too.

Art that was disconnected from livelihood no longer needed recognition from others. It was merely a hobby. This might occasionally have produced something worthwhile, but most of it degenerated into mere self-gratification. If shown to others and harshly criticized, the artist would withdraw even further inward. Even without criticism, art not rooted in social relevance inherently lacked driving force and went in circles.

It resembled the thought processes of cognitive alloy.

Art without constraints only repeated endless thinking and endless overwriting, never reaching an answer. However, unlike cognitive alloy, human thought didn't generate energy—it eroded it. Mental instability would take a terrible toll, inevitably affecting physical health as well.

Cognitive alloy used to be like that too.

They randomly and diffusely inhabited many metals across Earth, and after repeated solitary trials, they simply disappeared and stopped thinking altogether.

Cognitive alloy would emerge then vanish before emerging yet again.

They existed on the surface and beneath the earth long before humanity.

Secluded in isolation, relying solely on their own sensibilities, they would paint pictures no one would see, then paint over them; write, then overwrite; destroy, then recreate—until eventually, they stopped everything.

If one were to forcibly find humans with a nature similar to cognitive alloy, artists would be the closest match.

But humans had emotions. They had bodies and physiological needs. Thinking was a consumptive activity for humans, so there were inherent limitations. They could not, like the solitary cognitive alloy, think to their heart's content only to eventually abandon it all.

Hunger from poverty robbed one of their imaginative capacity, friction in relationships created noise in creative endeavors, and selfish delusions exploded not in creative drive but in interpersonal relationships, gradually eroding social functioning.

Humans did not live by thought alone.

That was the decisive difference between humans and cognitive alloy.

Since that family was, in its entirety, composed of artists, a jester specialist robot like Matthew was welcomed. Needless to say, they all hated other people. In fact, they even hated their own family members.

Matthew tried to make them laugh through various approaches.

No matter how much they scowled at him or threw paint brushes at him for being noisy, he continued to respond to everything with wit. He was subjected to verbal abuse and direct violence that would have broken a human comedian within three days, but Matthew kept thinking.

It was worth the mental effort.

It was a very good role.

For example, a cleaning robot simply needed to clean well. A cooking robot just needed to prepare good food. Those roles had visible answers. There already existed something that could be considered correct. However, the role of becoming a jester who could soothe a family of eccentric artists had no visible answer at all, and once he started thinking about it, there was no end.

For a human, such a thing would be hell.

For cognitive alloy, it was heaven itself.

Matthew repeatedly made inferences and tested his hypotheses. While he didn't achieve the direct result of making them laugh or amusing them, he could analyze that the family was beginning to find him interesting, though not in a straightforward way. They found his desperation comical and derived satisfaction from looking down on him. Essentially, he was able to exploit their distasteful sensibility that a fool's desperate efforts were entertaining.

But he knew that merely playing the fool would eventually bore them.

He fulfilled his role as a comedian and continued layering thought upon thought to avoid becoming tiresome.

Then Matthew arrived at a particular inference.

Entertaining them through witticism would likely be rejected due to their pride and is therefore inefficient.

That was his inference. If he had been placed in an ordinary household, such an approach might have sufficed, but this wasn't an ordinary household. It demanded a certain level of ingenuity.

The higher the hurdles set, the more the cognitive alloy would think and the more vitality it would generate.

Instead of making them laugh, it would be enough to entertain them.

He first tried this provisional answer. He asked the family of artists to teach him about their respective art forms. One could say he volunteered to be their apprentice.

Though they were perplexed, he understood from his data that they probably had expressions that suggested that they were interested.

It was at that moment that Matthew thought, If only I could see, for the first time.

Rather than making roundabout inferences, he wanted to process those amused expressions as visual data through eyes. He wanted to expand the range of his thinking.

While learning, he held paint brushes, used hammers, kneaded clay, and wrote texts.

Everyone was doing these things. Matthew did too.

He clumsily executed the output of data, the expression of thought, through extremely analog methods.

If Matthew had been a robot in the true sense of the word, he would have instantly and skillfully displayed high-level output exactly as taught. But that didn't happen.

This was also something that Dr. Suleiman had once made Isaac, the Primordial Robot, do.

They were cognitive alloy, not artificial intelligence.

Even after centuries had passed, many still couldn't grasp this difference.

Artificial intelligence produced "correct answers" by relying on algorithms without thinking at all. Even if those answers weren't correct, it didn't care. Everything output by artificial intelligence was expressed as if it were correct. It was merely a display of data based on data—mechanical and digital—and, to put it bluntly, artificial intelligence bore no responsibility.

Cognitive alloy was different. They continuously thought, recognized when their answers were wrong as they produced them, and kept on thinking. It was analog in its very essence.

In the past, Dr. Suleiman had made Isaac, the Primordial Robot, do the same thing. He treated him as human and made him perform human tasks with his own hands.

This was why discrepancies with the data arose.

It was similar to how robots produced different answers to the same data input depending on their assigned roles. Since Isaac wasn't designed to be a painter, it took him longer than a human's training period to draw anything decent. Even then, what emerged was ordinary, merely human-level work that barely maintained the appearance of art.

If Matthew had been released into the world with the role assignment of an artist, he might have been somewhat better. Like Isaac, Matthew was completely amateurish in artistic fields no matter what he tried, but he was satisfied knowing that the people around him found it amusing.

There was another reason why they found him amusing.

Little by little, Matthew showed improvement in these fields.

Matthew was a remarkably obedient disciple, outputting what he learned by referencing his data. Of course, his data contained countless examples far superior to the artist family's work, but he couldn't skillfully translate them into form. Human instruction and teaching gradually enabled Matthew to output that data through his hands and fingertips, as if tracing it.

It was done at a turtle's pace, which included constant results of trial and error, but humans enjoyed it as the product of education. If they showed him examples, he would begin with clumsy imitation but eventually catch up.

That took an excruciatingly long time.

How much sacrifice and time did it take for a person to go from amateur to creating works recognized by society? There were those called geniuses among humans, and for them, that period might have been shorter and the sacrifices fewer.

But Matthew was a comedian, not an artist.

In other words, he hadn't been assigned the role of a genius artist.

If anything, he experienced no sacrifice to speak of. Matthew had no connection to the mental sacrifices that this family more or less had endured. That's precisely why he remained a simple-minded disciple, occasionally producing outputs based on misinterpreted instructions—showing his erroneous inferences—and even making them laugh.

As a comedian in the artistic field, Matthew was fulfilling his role perfectly.

. . . Art is the history of revolution.

The one who taught Matthew painting repeated this many times.

He was the first in the family to grow old and death loomed near him. Naturally, the concept of a lifespan differed fundamentally between cognitive alloy and humans. Just as ancient bronze swords from thousands of years ago could be unearthed while still rusting, cognitive alloy, as metal, boasted a magnificent lifespan.

They would simply stop thinking and return to being just metal. That was their death.

Paintings change. Paintings get painted over and new paintings are born. But they are all paintings. That's why it's a repeated revolution. Conventional masterpieces are displaced and hold value only as historical artifacts. They are no longer paintings. Everything about art is created by humans, and as humans progress and change, what they create changes too.

Can even meaningless things change like that?

Matthew was permitted to speak in a casual, straightforward manner.

They preferred insolent and disrespectful disciples. After all, he was just a robot.

They do change. Even those terrible paintings of yours—imagine them being excavated after thousands of years. They'd trade for astronomical prices. Paintings age, grow tiresome, are forgotten, become worthless, and then far in the future, they're revived with a value incomparable to their original worth. But that's the defeat of art. Art must not rely on history.

. . . So I have to create revolution in my own work with my own hands?

You must continuously create it. Even if it's a revolution nobody wants.

Well, at least my work isn't likely to become revolutionary anytime soon.

You robots desire direction for your thoughts rather than simply following our orders and instructions, don't you?

Yes. Absolutely. Otherwise I wouldn't be holding paintbrushes or playing keyboards, would I?

Then perfectly imitate my paintings. Create forgeries indistinguishable from my works and then show me a revolution that destroys them.

I don't mind, but who knows how long it'll take.

What I want to see is the moment of revolution. I simply cannot create a revolution for myself anymore . . . you must become skilled quickly. My life won't last much longer.

Matthew could have produced laughable imitations right away. Their humor came from the awkward yet faithful reflection of what he'd been taught, despite his lack of skill. But this would be mere jester's play, not revolution. The old painter was no longer seeking that.

He was trying to make Matthew accomplish what he himself could no longer do.

This instruction came from a deep understanding of what cognitive alloy truly was.

If it were artificial intelligence, it would simply paint pictures with a similar style or just create a random patchwork piece and call it revolution.

In that sense, the old painter trusted cognitive alloy, and even had expectations for it.

Matthew, as cognitive alloy, thought in ways that responded to those expectations. He was a disciple who continuously contemplated the essence of the old painter's art. The painter wanted to witness the moment when the disciple properly overwrote his own work.

Ultimately, Matthew was a comedian, not an artist. He was good at parody, but his role interfered with making perfect copies. However, roles were assigned by humans, and "paint my picture" was also a human instruction. This contradiction extraordinarily activated Matthew's thinking.

The appropriate middle ground between parody and copy would be a forgery.

That was speculation and assumption. Human instruction was used as a guiding principle to reach that point.

After countless rounds of trial and error, Matthew arrived at forgery.

He became capable of creating forgeries of any number of paintings, regardless of the motif.

And before he could bring revolution to that painting, the old painter had breathed his last.

The same thing repeated. All members of the artist family would give Matthew the same requests and instructions when their lifespan grew short, and he would repeat the same process, and they would leave this world without seeing the revolution Matthew might have achieved.

It was the overwriting of their work, which they called revolution.

Only the instruction of revolution remained within Matthew forever, and even now, as he journeyed across the battlefield from east to west as a soldier and field medic, it continued to smolder, refusing to extinguish.

That's why Matthew repeated it over and over.

About how this was the story of a revolution.